Today is October 7th, which most of the world will refer to as Wednesday; but those who know its significance know it as a day when the world could have turned out very differently. Dig deep enough and you can find such events on any day of the calendar; but rarely are there days of decisive action in the face of uncertain times, of reverberating victory despite inevitable defeat, as happened on this day, nearly four and a half centuries ago.

Today is October 7th. Today is the day when the Ottoman Empire, the fearsome juggernaut, the unstoppable superpower, its soldiers and ships poised to conquer Europe, were stopped in the last medieval naval engagement in European history.

Today is the Feast of Our Lady of Victory, and the 444th anniversary of the Battle of Lepanto.

Torchlight crimson on the copper kettle-drums,

Then the tuckets, then the trumpets, then the cannon, and he comes.

Don John laughing in the brave beard curled,

Spurning of his stirrups like the thrones of all the world,

Holding his head up for a flag of all the free.

Love-light of Spain–hurrah!

Death-light of Africa!

Don John of Austria

Is riding to the sea.

~ “Lepanto,” by G. K. Chesterton

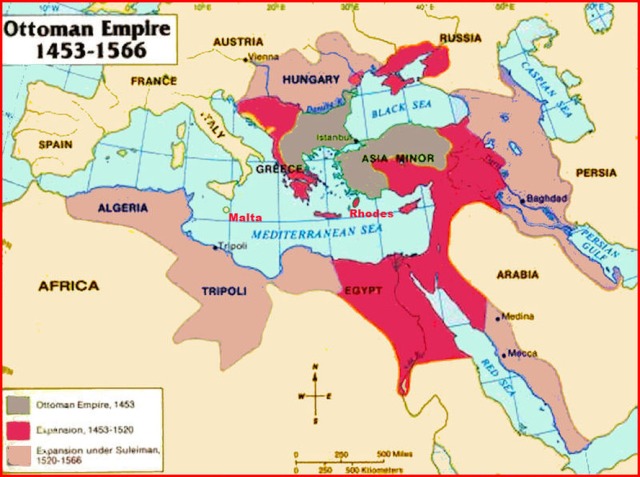

Ottoman Turks: keeping cartographers busy since 1299.

It is 1571, and Europe is in crisis. It has been just over a century since the fall of Constantinople, which could be seriously compared to 9/11 in how it changed the world. The last time foreigners had conquered that land had been the Romans themselves; and now, the last continuation of Roman rule, in the form of what we today call the Byzantine Empire, was gone. The Ottoman Turks moved in, and even as they enjoyed their spoils they continued building up for more. They were the equivalent of Soviet Russia for their time, a great shadow looming over Europe, an inevitable specter of war.

“Hey, French guys, you kicked our cousins’ butts a lot over the last few centuries. Now that your kings have gotten lazy, how about we make an agreement where you help us fight YOUR cousins? We promise not to attack you until it’s convenient for us.”

Europe, in comparison, was fractured. I don’t just mean the rise of Protestantism; that just poured more fuel on the contentious fires that already blazed there. Instead of uniting against a common foe, petty differences between nations (or just between rulers) led some to strike deals with the Turks against others. France even joined in an alliance with the Ottoman Empire, which wasn’t looked on with favor by, well, pretty much everyone else.

Left unchecked, the Turks were certain to overrun Europe — or, at least, the southern portions. Many of the Mediterranean Catholic states began their own, temporary alliance, known as the Holy League. France, of course, stayed out of it. The Holy Roman Empire decided to maintain its ongoing truce (probably a wise move, because the HRM was the main block against Turkish land-based expansion, and due to Protestant revolts didn’t have the manpower to launch a full invasion), while Portugal didn’t have any forces to spare because of its own conflicts with Muslim nations.

Many of the member states of the Holy League aren’t familiar to modern ears: places like the Kingdom of Naples, the Duchy of Savoy, the Republic of Genoa, the Papal States, and more. However, considering who controlled what then versus now, you can think of it as Spain and Italy deciding to agree on something more important than yelling at each other over whatever sport they played before soccer was invented.

They have dared the white republics up the capes of Italy,

They have dashed the Adriatic round the Lion of the Sea,

And the Pope has cast his arms abroad for agony and loss,

And called the kings of Christendom for swords about the Cross.

The cold queen of England is looking in the glass;

The shadow of the Valois is yawning at the Mass;

From evening isles fantastical rings faint the Spanish gun,

And the Lord upon the Golden Horn is laughing in the sun.

It was the middle of August when things finally got started. It was a Saturday, to be precise; the 14th of August, and presumably a warm summer’s day when the riders got to Assisi. They bore an important item: a blue banner depicting Christ crucified, blessed by Pope St. Pius V, the same pope Chesterton described above. Whether it was hot outside or not, it was cool inside the Basilica of St. Claire, where that banner was formally presented to, and accepted by, the chosen commander for the Holy League’s forces. Don John of Austria was going to war.

Don Juan di Austria wasn’t an easy choice to command the fleet. In addition to having a multitude of people jockeying for the honor, Don Juan had an additional stigma attached. He was the illegitimate son of Charles V, perhaps the most well-known Holy Roman Emperor aside from Charlemagne himself. That also made him the half-brother of Philip II of Spain — yes, the same Spanish king who tried invading England with the Armada — and part of Philip’s terms for backing the League was that Don Juan be placed in command.

Dim drums throbbing, in the hills half heard,

Where only on a nameless throne a crownless prince has stirred,

Where, risen from a doubtful seat and half attainted stall,

The last knight of Europe takes weapons from the wall,

The last and lingering troubadour to whom the bird has sung,

That once went singing southward when all the world was young.

In that enormous silence, tiny and unafraid,

Comes up along a winding road the noise of the Crusade.

Strong gongs groaning as the guns boom far,

Don John of Austria is going to the war.

If Don Juan was the last knight of Europe, he wasn’t a shining example of it. However, this was the last truly medieval battle in the Mediterranean, and arguably all of Europe. Gunpowder had been introduced, but tactics were still taking new weaponry into account; and cannon were not much use in pitched naval battles at this time. The Battle of Lepanto was fought with galleys instead: oar-driven ships, with little maneuverability and little space for the clumsy cannon of the age. While ships were armed with cannon and some even bore firearms, when galleys meet they simply move at each other as if the sea were merely an over-soaked battlefield. Perhaps it’s fitting to call him the last knight simply because Lepanto marked the end of that age of warfare.

Regardless of his qualifications for that title of knight, last or no, Don Juan was the proper choice for the job. His vices were many, but they did not include cowardice or incompetence. Don Juan, once appointed commander, was reportedly the reason why the disparate and disagreeable members of the League were able to work together.

The League and Ottoman fleets met in the Gulf of Patras, in the Ionian Sea. Nearly five hundred ships closed on each other, with most of the fighting happening through boarding actions. The League had 212 ships, while the Turks had nearly 300. The Christian forces were comprised of 28,000 soldiers, over a third of which were Spanish regulars, in addition to their 40,000 sailors and oarsmen (though most of the oarsmen were convicts and a few of them slaves, none of whom were intended to participate in the fighting). The Ottomans, on the other hand, had 34,000 soldiers and 13,000 free and very experienced sailors, with almost all their 37,000 oarsmen provided by Christian slaves.

Even 444 years later, it’s still considered one of the largest battles in history, if not the largest of them all.

A painting of the battle that hangs in the Vatican Library.

During the battle, Don Juan and his opposite, Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, met on the field of battle as their two flagships became the center of fighting. Each ship was reinforced with troops from other galleys, and the League was repelled three times. Finally, on the third attempt, the Ottoman flagship was taken after an hour of very bloody fighting. Müezzinzade Ali Pasha was beheaded, though Don Juan wanted him taken alive; and with his death, the Ottoman forces broke.

A replica of Don Juan’s flagship, the Real, constructed for the 400th anniversary of the battle. Photo by David Merrett, via Wikipedia.

On the day of the battle, Pope St. Pius V was praying in his private chapel when he received a vision of the victory, which was attested during his canonization process. Pius V had asked all Catholics to pray the Rosary for victory, and it is thought that he was so specific in requesting this prayer, not a common practice at the time, because he was a Dominican. St. Dominic is credited with spreading this prayer in his missionary work, and teaching people to pray it for the conversion of sinners.

While it is attested that Pius V knew of the end of the battle the moment it happened, long before any word could have reached Rome, details are sketchy on exactly what vision he received. One thing is certain, however: the saint knew that this victory was due to so many people praying the Rosary and invoking Our Lady. He established October 7th as a Marian feast the following year, and the Church has celebrated it ever since — even if it’s no longer as popular to refer to today as the Feast of Our Lady of Victory.

The victory was a resounding blow to Ottoman expansion; they had not suffered a major naval defeat in two centuries, and the morale shift was electrifying across both sides. The Turks were not out of the game by a long shot; Europe was still fractured, the League was soon disbanded, and the Ottomans were a threat for centuries to come. Battles continued to be fought, and Christian lands taken. Some scholars argue against the idea that Lepanto was truly a resounding defeat for the Ottoman Empire.

Yet Ottoman naval power no longer ruled the Mediterranean. They may have conquered the last remnants of the Roman Empire, which once ruled those waves so thoroughly that it was dubbed the Roman Lake; but there was not, and would never be, an Ottoman Lake. Their greatest fleet had been met and destroyed, and the loss of so many experienced sailors crippled their naval power for a generation. The outnumbered Christian forces lost 7,500 men and 17 ships; the supposedly unstoppable Ottoman fleet lost 20,000 men and nearly two hundred ships, most captured intact and with their slave crews subsequently freed.

Comparing their military might before and after Lepanto leads to only one conclusion: Don John of Austria, the last knight of Europe, had crippled his enemy. While they maintained their then-current lands, they would never again threaten Italy with more than the occasional pirate raid.

The Pope was in his chapel before day or battle broke,

(Don John of Austria is hidden in the smoke.)

The hidden room in man’s house where God sits all the year,

The secret window whence the world looks small and very dear.

He sees as in a mirror on the monstrous twilight sea

The crescent of his cruel ships whose name is mystery;

They fling great shadows foe-wards, making Cross and Castle dark,

They veil the plumèd lions on the galleys of St. Mark;

And above the ships are palaces of brown, black-bearded chiefs,

And below the ships are prisons, where with multitudinous griefs,

Christian captives sick and sunless, all a labouring race repines

Like a race in sunken cities, like a nation in the mines.

They are lost like slaves that sweat, and in the skies of morning hung

The stair-ways of the tallest gods when tyranny was young.

They are countless, voiceless, hopeless as those fallen or fleeing on

Before the high Kings’ horses in the granite of Babylon.

And many a one grows witless in his quiet room in hell

Where a yellow face looks inward through the lattice of his cell,

And he finds his God forgotten, and he seeks no more a sign–

(But Don John of Austria has burst the battle-line!)

Don John pounding from the slaughter-painted poop,

Purpling all the ocean like a bloody pirate’s sloop,

Scarlet running over on the silvers and the golds,

Breaking of the hatches up and bursting of the holds,

Thronging of the thousands up that labour under sea

White for bliss and blind for sun and stunned for liberty.

Vivat Hispania!

Domino Gloria!

Don John of Austria

Has set his people free!

Pingback: The Battle of Agincourt | The Catholic Geeks

Pingback: How To Make Catholics Look Stupid: A Lethal Force Fisk | The Catholic Geeks

Pingback: Lepanto – Little Squirrel Books